Fanny: The Right to Rock

2021

Director : Bobbi Jo Hart

By Arturo Arrerondo

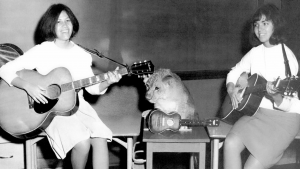

Fanny was an all-female rock band founded in 1969 by the Millington siters June and Jean on guitar and bass, respectively, and their school friend Brie Darling on drums and percussion. All three are Pinay-Americans who grew up in California and were capable vocalists. They practiced almost endlessly, wrote songs together, and played enough gigs to attract the attention of Warner Bros. Records imprint Reprise Records (the longtime home of Neil Young and home of criminally under appreciated 1990s power pop band The Katydids) in 1970, before Brie was forced to leave the band and the Millington sisters recruited drummer Alice De Buhr and keyboardist Nickey Barclay as Brie’s replacements. They were a popular opener for the heavy hitters of their day, but never had a major hit, and so were mostly forgotten after releasing 5 albums in 5 consecutive years. Now, there is a documentary about Fanny.

The big, recurring problem with music documentaries, especially of rock bands, is that they often lean towards hagiographies. That likelihood increases if the subject is dead. The Wrecking Crew can be forgiven for its hero worship moments, as the son of one of the legendary session band members was the driving force. Muscle Shoals, unfortunately, has no such excuse. Maybe a documentary about Brian Wilson or Burt Bacharach would be justified in that approach, but I digress. Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me is perhaps the rare example of a band documentary that isn’t just an hour and a half about how great their music was.

It would seem filmmaker Bobbi Jo Hart was well aware of this problem and carefully avoided it at all costs for Fanny: The Right to Rock’s lean 96-minute runtime. Right away I noticed the talking heads segments weren’t token celebrities singing praises, but instead fellow musicians – Earl Slick, Gail Ann Dorsey, Joe Elliott, Todd Rundgren, Bonnie Raitt, and John Sebastian all feature in the incredible lineup – championing the musicianship, artistic credibility, and forgotten victories of a 4-member all-female, 50% Pinay-American rock band (they were originally a 100% Pinay-American trio) from the 1970s that opened for Deep Purple and held jam sessions in their home with members of The Band and Little Feat. It also helps that the members of Fanny are all still living and still energetic about their experiences despite the cynical nature of the music industry. A rather brilliant creative choice was to feature a handful of Fanny’s songs but not to the point of overpowering the interviews or band members’ narration; another rare turn for a music documentary that Bobbi Jo Hart successfully pulled off.

Of the 5 members of Fanny, 4 took part in the documentary, and despite the documentary only being an hour and a half in length, ample time is devoted to each member, their backstory, and present situation. Each one has a unique journey they divulge whether it be motherhood, career, or some combination thereof. Their memories and emotions related to their time with the band are of course emphasized, as 2 members floated in and out of the band before 2 other members departed permanently causing the disbandment. There is a pervasive strain of melancholy throughout the interviews, justifiably so, that keeps the documentary from drifting into a nostalgia-fest. However, there is also an irrepressible optimism to balance the regrets and self-criticism; the band seem overjoyed to finally have the chance to tell their story beyond that of an “all-girl rock band” as well as reunite to record new music together. While the band maintain a grounded approach to their accolades, they also stress repeatedly that no press at the time ever mentioned they were Pinay-American and delve into how that constant omission of fact made them feel invisible.

A motif throughout the film is how much David Bowie enjoyed the band, with many interviewees recalling his statement about Fanny being “one of the most important bands in American rock… buried without a trace.” It highlights the authenticity of the band, the documentary, and the interviewees who genuinely get distracted by tangents about their appreciation of Fanny. Joe Elliott of Def Leppard in particular espouses a wide-eyed, almost child-like endearment of Fanny’s guitar work. If there are any flaws to the film, they at least do not detract from the overall story. During the credit roll, Fanny’s music post-reunion is featured heavily and everything becomes a bit too saccharine, but that’s not a deal breaker. Also, the very short segments of an anonymous young woman featured listening to Fanny’s records are unnecessarily on-the-nose given that Fanny’s influence on future all-women acts is stated plenty and plainly, but it’s also a minor flaw given that those segments, one of which opens the film, only total about maybe a minute and a half. Still, that’s a minute and a half that could have featured more of Earl Slick’s or Gail Ann Dorsey’s interviews or even more of Joe Elliott commenting on his favorite songs. Hopefully, this documentary will right the wrong of Fanny’s obscure status, and it deserves to be seen as much as their music deserves to be heard.

Right to Rock is part of film lineup for the 2021 Atlanta Asian Film Festival, Oct 2-3, 2021.

RATINGS: 4/5